LITERARY BORROWING AND THE BIBLE 02

HOW THE BIBLE BORROWS STORIES 02.

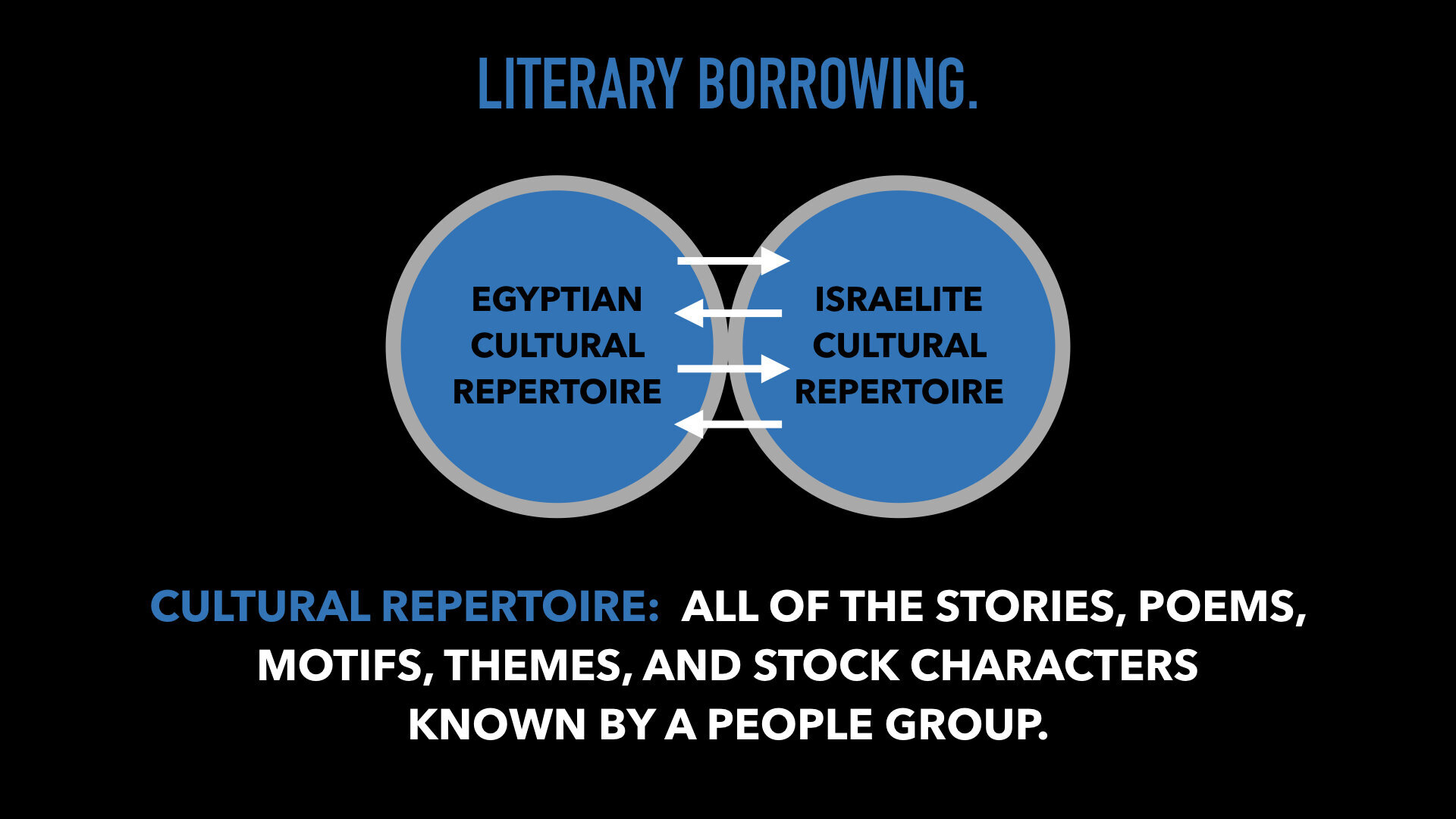

Okay so if you read my post Literary Borrowing and the Bible 01, you understand that people’s shared literary collection, or cultural repertoire, is stable but also slowly changing. The repertoire changes as it encounters new literary material. Let’s talk about how that happens—how cultural repertoires gain new influences. There are three primary ways that culture borrows literary elements and integrates the new influence into its own literary repository: Direct, Indirect, and Quasi-Direct borrowing. The first is called direct borrowing. Direct borrowing is when a core story line, literary motif, or literary theme is taken from another culture’s repository in its entirety. This is the wholesale lifting and rewriting of a core story. The fundamental literary stations are kept, or core plot points or events of the story, but assigned a new function to serve a writer’s purpose.

DIRECT BORROWING.

An excellent example of direct borrowing is the story of Potiphar’s wife in the Joseph cycle in Genesis. The borrowing is “direct” because it copies the core structural elements of an Egyptian narrative called “The Tale of Two Brothers.” When we read the Genesis account of Joseph alongside “The Tale of Two Brothers,” it becomes evident that these two documents share a common storyline. Since scholars know the Egyptian text predates the Israelite text by up to thousand years, we know the biblical writer borrowed the story from the neighboring culture of Egypt was directly. DIRECT BORROWING.

LITERARY STATIONS PROVE BORROWING.

“A Tale of Two Brothers” is full of commonalities to the Joseph story of Potiphar’s wife in the Bible because it is the same core story. It goes something like this:

1) Two men, one is the employee and closest confidant of the other.

2) A young man of extraordinary stature and sexual attractiveness.

3) A scene where the young man is in the house alone with the wife.

4) The wife tries to seduce young man after noticing his attractiveness.

5) Young man refuses out of integrity.

6) Insulted, the wife fakes abuse and accuses the young man of rape.

7) The young man pays a shameful price but is then vindicated by rising to power.

Notice in this example, how the Israelite author has appropriated the core story line into a narrative meaningful to an exilic people. The biblical account becomes a story about a disenfranchised Hebrew who rises to the position second only to the king. The brilliance of the Joseph cycle, then, is not originality but artistic borrowing. The Egyptian text is a story for entertainment, about two brothers who fight because of the guile of the elder brother’s wife, where one man loses his phallus in proving his innocence (which really defeats any intended resolution to the narrative). “A Tale of Two Brothers,” being the earlier text, already has its own ideology as well its respective commentary on divine purposes.

THE ART OF LITERARY THEFT.

The biblical scribe has taken a core story and changed it beautifully to show that Yahweh sees the righteous sufferer and eventually brings about the good of those who act with prudence. In this artful retelling, the biblical writer lifts a core story line and uses it to generate a powerful story to encourage and envision a dispersed people. This is a marvelous accomplishment which evinces high literary skill, which brings us to some important implications about borrowing in the Bible.

Here are some takeaways for Modern Readers:

1. For every story we have there are probably parallel stories we have lost. And so we should hold biblical literature, and particularly reading it as historical, loosely and humbly. Who is to say more of the stories of the Bible do not have parallels we have never uncovered? The more I study the ancient world the more I find core stories and floating motifs being used and reused in a larger scribal culture. That’s okay. This is simply how ancient scribes compiled literature.

2. The theological importance of biblical stories is what the writers want you to consider. Biblical writers could care less about passing on the past for some modern, western archive of human civilization. Theirs is a project of naming God in a way that helps a post-exilic Israel be self-aware and unified in purpose as they seek to represent God’s character in the world. They have no problem borrowing stories to name God, and in fact, sometimes they deliberately borrow stories to highlight how Yahweh is different.

3. Who is God and what do the people of God look like? This is a question that will be far more helpful than “what really happened?” because a large part of ancient writing is the art of borrowing old stories to say something new. For instance, there is not a strong moral statement about either of the brothers in “A Tale of Two Brothers” nor a helpful naming of divinity, as far as I can tell. And on the other hand, I have looked to Joseph many times in my life when I have felt abandoned, or betrayed, or overlooked, or caught entrapped by my own arrogance. Joseph’s is a path that can lead to wisdom in speech and conduct— he is an exemplary character. Even more, Yahweh was with Joseph. The writers want you to know that Yahweh was with Joseph far from home and far off track— what better message to a people in exile or trying to regain solidarity after returning to a forgotten past. You can learn “who is God” and “who is Joseph” and the answers to these questions can guide your own life. So go ahead, do your own direct borrowing.

————————————————————————————————————————

HEY HEY!

To support TEXT aND ROCK, do us a solid and grab some swag at the shop, or try our audio book, HOUSE OF THE WORLD. The tee’s are so pirate, the story is the greatest one ever told…

We have more stuff in the digital press and more stuff coming— all designed to take you farther faster in understanding the Bible in its context through literature and archaeology…and eat sermons for lunch.

TEXT AND ROCK ON!!